This 1942 sculpture by Michael Lantz, 17-feet long, is meant to suggest a heroic figure (the FTC) restraining violent and untamed American commerce.

Author: Steven Levitsky

If you liked the old computer game, “Minesweeper,” then you’re ready to take on Hart-Scott-Rodino (HSR) filings for antitrust review of mergers & acquisitions. Both have rules. And both can produce unexpected catastrophes even if you think you’re following the rules. In fact, major clients, advised by major law firms, have been hit with hundreds of thousands of dollars in fines for mistakes that no one thought of at the time.

Let’s start with the 50,000 foot view of HSR compliance. You might know the basics: (a) you need to make an HSR filing when one side of the transaction has sales or assets of at least $16.9 million; (b) the other side has sales or assets of at least $168.8 million; (c) the transaction size is greater than $84.4 million; and (d) no exemptions apply. (These are 2018 figures).

An example to consider

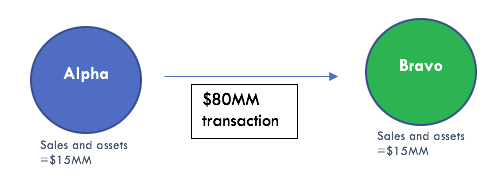

Here’s an example of how things can work out badly. Let’s assume you get a call from the CEO of your client, Alpha Co. Alpha Co. is a small and relatively new company and the CEO tells you:

- Alpha’s annual sales and assets are $15 million.

- Alpha plans to buy $80 million of the voting securities of Bravo Ltd. (Alpha’s borrowing $65 million to do the deal.)

- Based on this, he wants to know if they need to make an HSR filing.

Applying what you know, you conclude that the “size-of-person” and “size-of-transaction” tests are both not met, so no HSR filing is required. Alpha Co. goes ahead and closes the deal.

Three months later, your client hears from the FTC. The FTC tells them that they violated the HSR Act by not filing, and that the fine is $41,484 per day, or $3,733,560 in all. What went wrong? (We’ll explain in detail in Point 2.)

But generally, what went wrong is that the 50,000 foot view is not enough. HSR rules are extremely technical and, some would say, not exactly logical. A lot of HSR terms don’t have a common sense meaning. You need to check and cross-reference the definitions and rules. And these, by the way, are not organized in any friendly or rational way, but seem to read like the Tax Code.

Here are some basic HSR concepts that might help you avoid the worst minefields.

- What are the basic HSR tests?

There are two tests to see if a filing is required.

First, “size-of-person.” Normally, you don’t need to file for the antitrust enforcers unless one side of the deal has sales or assets of at least $16.9 million and the other side has sales or assets of at least $168.8 million. (This are 2018 figures; these numbers change every February.)

But, as we’ll see soon in Point 2, the size-of-person test does not mean the size of the transaction party. Instead, it means the size of the buyer’s entire business group, or everything under the control of its highest entity (see §5). Don’t fall into the trap of measuring an incomplete control group.

Second, the “size-of-transaction” must be over $84.4 million (again, this is 2018; the numbers change every February). But there are several other filing thresholds that cover more purchases in the same target and could require successive filings. These include $168.8 million; $843.9 million; 25% of the target — but only if the size-of-transaction is more than $1.688 million; and 50% of the target — or control. Once you get control, you can buy as much more of the target as you want without ever filing again.

But, as we’ll see soon in Point 2, the “size-of-transaction” does not really mean the size of the transaction. Instead, it means (1) the combination of existing holdings and planned acquisitions, (2) that the entire buyer control group will have in the target control group after the deal closes (see §2). This includes voting stock acquired years before, that has to be analyzed at its current value. Don’t fall into the trap of measuring the wrong amount.

- What is an “ultimate parent entity” and why does it matter?

The “ultimate parent entity” is the top controlling entity of an entire business group.

The “ultimate parent entity” matters to your antitrust filing for the following reason. The purpose of the HSR filing system is to let the antitrust agencies know of significant shifts in competitive power. As a result, they don’t care about the names on the contract, which may be only small subs or special purpose vehicles. The antitrust agencies want to know what is really happening in terms of changes of competitive power.

To give the agencies that information, you must identify the entire control group of your transaction party. You do this by tracing control upwards from the transaction party (Alpha Co., in our case) to the very highest control level of the business group. That entity at the top, that isn’t controlled by anyone else, is the “ultimate parent entity,” which can be a company or an individual. The “ultimate parent entity” makes the filing. Its collective size and holdings affect the “size-of-person” and “size-of-transaction” tests we discussed in Point 1.

Here’s an example. When Alpha Co. called, it told you that their deal looked like this:

This seems to be an insignificant transaction that doesn’t meet either the size-of-person or size-of-transaction test. Based on these facts, there did not seem to be any HSR issue.

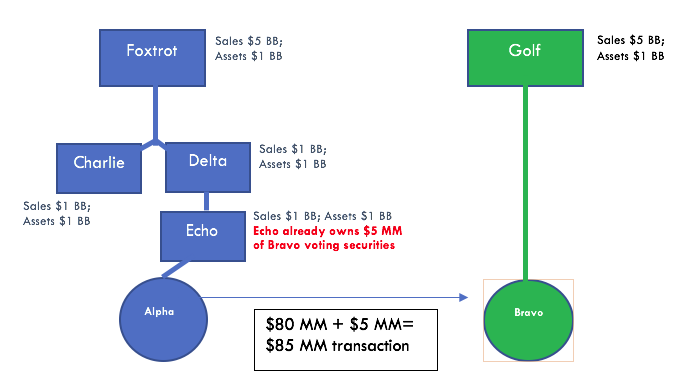

But once you start to ask the client about its structure, you find that both Alpha and Bravo are actually minor subsidiaries in much larger control groups, and that Echo, one of the related companies in Alpha’s control group, already owns $5 million of Bravo Ltd’s voting stock. This diagram presents the real picture, based on control groups.

With this more accurate information, the HSR picture has changed for two reasons.

First, this is now a deal where the buyer and seller control groups (measured by all the entities controlled by their “ultimate parent entities,” Foxtrot and Golf,) each have sales or sales of more than $1 billion. They more than meet the “size-of-person” tests that Alpha and Bravo alone did not.

Second, when you’re looking at the “size-of-transaction” test (which really means “post-closing holdings” for the entire buyer control group), you need to combine all the existing holdings that any member of the buyer control group already has in the target control group, plus what they plan to buy.

This means that this is not an $80 million transaction, as it first seemed. It is actually $85 million, because Foxtrot’s control group already owns $5 million held by its sub, Echo, and, with Alpha’s purpose, will acquire another $80 million. The combined holdings, after the deal, will cross the $84.4 million HSR threshold. Alpha and Bravo alone did not meet this test. Their control groups did.

- What does “control” mean?

This brings up the question of control. There are actually two separate tests for “control,” which, as we saw, are used to define the members of the control group, or those companies controlled by the “ultimate parent entity.” Again, HSR filings are based on control groups, not transaction parties.

For corporations, “control” means (1) holding at least 50% of the outstanding voting securities of a corporate, or (2) having the contractual power to name 50% or more of the directors.

For unincorporated organizations (like LLCs and partnerships), “control” means (1) having the right to at least 50% of the profits, or (2) having the right to 50% of the assets on dissolution.

NOTE: Because HSR control is set at 50%, not 51%, you could have two parties in “control” of the same entity.

- What types of deals trigger an HSR filing?

You need to make a filing when you acquire (not just buy): (a) voting securities; (b) assets; and (c) partnership or LLC interests.

Note: For partnership or LLC interests, you need to file only when you get control. Acquiring 49% of an LLC for $20 billion is exempt.

- What does “acquire” mean?

Why do we say “acquire” and not “buy”? Because you need to report the acquisitions no matter how you get them (unless you inherit them or they’re a genuine gift).

For example, you’re a very successful executive and you get dividends or options of voting stock every year as part of your compensation. Even though you don’t buy that stock, you are still “acquiring” it for HSR purposes. If the total value you’ll have (existing and planned holdings) will push you across the HSR filing thresholds (now $84.4 million), you need to file before you acquire the new voting stock.

- Are there any minimum size deals you don’t need to worry about?

Yes. Transaction values under $84.4 million don’t need to be filed. In fact, you can’t file them even if you wanted to.

- Does that mean that deals smaller than $84.4 million are exempt from the antitrust laws?

No, it absolutely does not.

The merger laws cover all transactions and forbid any merger where there is a reasonable probability that its effect could substantially harm competition. The fact that no HSR filing is required is not a free antitrust pass. The antitrust agencies have sued to block many mergers smaller than the HSR thresholds.

Potential harm to competition is measured by product market and geographic area. That means that the agencies could focus on a single product or small market area. For example, the Department of Justice once sued in Federal Court to block a $3.1 million merger that involved a chicken processing plant in Harrisonburg, Va.

You should always assume that the antitrust agencies will discover any unfiled merger, and that they might well chose to challenge any merger that could have anticompetitive effects.

- Are there any special rules for large deals.

Yes. If the “size-of-transaction” is over $337.6 million, then you can forget about the size-of-person test. You need to file – unless some exemption applies.

- What are exemptions?

The HSR rules allow you to subtract some types of asset acquisitions from the transaction amount because they seldom have competitive significance.

The leading example is the “ordinary course of business” exemption. Anything you buy for use in your business or production processes is exempt from HSR filings. That means, for example, that if an airline buys $5 billion worth of Airbus 380s, that transaction does not need to be reported.

There is a very large array of other exemptions. To name just a few examples, these include office buildings, apartment buildings, agricultural land, and reserves of oil, natural gas, shale or tar sands up to $500 million. Note, however, that there may be informal FTC interpretations of these exemptions that limit their use.

While the exemptions are listed as “exempt assets,” you can also use them when you acquire a company. A provision of the HSR Act allows you to “look through” the company to the underlying exempt assets and subtract them from the transaction value.

- Are there any exemptions for passive investors?

Yes. There is a provisions that exempts acquisition of up to 10% of voting securities of a target, regardless of the dollar amount. There is also a similar exemption, with its own restrictions, exclusively for institutional investors, who can acquire up to 15% of a target as long as it is not the same type of company as the institutional investor.

But this exemption is restricted to a passive investment only. The critical element here is that the buyer must have no intention, at the time of acquisition, to become involved in the management of the company. Examples of activity that bar this exemption include (a) trying to influence the target’s operations; (b) nominating a candidate for its board; (c) sending advice to the target on merger strategy; (d) soliciting proxies; (e) competing with the target; or (f) having anyone connected with the investor serving as an officer or director of the target.

If you plan to use this exemption, you need to be very careful to examine the buyer’s intent, measured at the time the investment is made. You must also make sure you correctly measure the degree of ownership across the investor’s entire control group, to make sure the “ultimate parent entity” doesn’t cross the 10% line.

*

We hope this basic outline helps you understand some of the minefields that affect HSR practice. In later articles, we’ll explain in some detail some of the complications on these concepts. Good luck!

The Antitrust Attorney Blog

The Antitrust Attorney Blog