Author: Luke Hasskamp

This is the second of a series of articles examining some of the interesting intersections between the law and baseball, with a focus on baseball’s exemption from federal and state antitrust laws. (Though, like the first article, this one does not quite reach the antitrust issues, as the initial challenges were brought under contract law.)

The first article looked at some of the early conflict between professional baseball players and team owners of the National League, which largely originated from the owners’ adoption of the “reserve clause,” which effectively tied a player to a single team for the entirety of his career, subject to the team’s discretion (and ten-days’ notice). Naturally, this led to litigation, particularly as other leagues emerged that sought to compete with the National League. The National League sued several players who tried to jump to the Players League—and the players won resounding victories in those early cases, with courts refusing to find the one-sided contracts to be enforceable on the ground that they were indefinite agreements and/or lacked mutuality.

The third part of the series is Baseball Reaches the Supreme Court.

The fourth part of the series is baseball’s antitrust exemption.

The fifth part of the series is Touch ’em all, Curt Flood.

By the time the 1890 season ended—with the National League champion Brooklyn Bridegrooms and the American Association champion Louisville Colonels participating in a best-of-seven game “world” series that ended in a tie—it seemed that the reserve clause was doomed. But forces conspired to give the teams, yet again, the upper hand.

To begin, the Players League ended its first season as a financial failure, causing the League to disband. This relieved the National League of a major competitor. The National League received more good news following the 1891 season, when the American Association, another professional league, failed. This meant that, once again, there was only one professional league in town. Thus, even though the players had won important cases invalidating the reserve clause, they had nowhere else to play, which would remain the case for the next decade.

Things got a little more interesting in 1901 with the arrival of the American League, which emerged as a serious competitor. Indeed, the National League had instituted a per player salary cap of $2,400, while the American League offered salaries of up to $6,000, causing dozens of players to switch leagues.

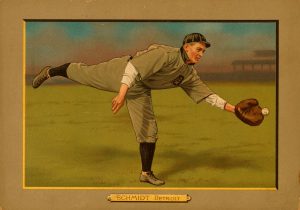

One such player was Napoleon “Nap” Lajoie, a star player for the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies. Indeed, Lajoie was one of the first superstars of the game and was highly sought by the upstart American League. (Indeed, he refused to take a bad photo.) Despite his contract with the National League, Lajoie signed with the new American League team in town: the Philadelphia Athletics (which was to be managed by Connie Mack, who remained the manager of the Athletics for an incredible 50 years—the longest-serving manager in Major League Baseball history—amassing records for wins (3,731), losses (3,948), and games managed (7,755)).

The Antitrust Attorney Blog

The Antitrust Attorney Blog